Cultural Adjustment

Adjusting to a new culture can be like riding a rollercoaster. One day you're up - exhilarated by new experiences, confident in your abilities, and enjoying the thrill of the ride. And the next day you're down - fearful of the unknown, disoriented, tired, and ready to bail.

Just like riding a rollercoaster, knowing what to expect and developing some coping strategies will help make navigating and adjusting to a new culture a more enjoyable experience. Hang on, it is going to be an exciting ride!

What is culture?

Culture is the total sum of what a particular group has created together, shares, and transmits.

| Maximizing study abroad: A students’ guide to strategies for language and culture learning and use.

Metaphors for culture

Culture as an iceberg

Culture as an iceberg

The iceberg is often used as a metaphor for culture. It is large, developed over many years, and constantly changing. This metaphor also highlights how there are visible aspects of culture – food, clothing, art, language, etc. – that are easier for a newcomer to see and navigate. However, like an iceberg, the larger and more difficult to navigate aspects of a culture are the invisible parts beneath the surface – the ideologies, notions of self, concepts of family, humor, etc. – that inform the way members of a group think and behave. It takes more time and effort for a newcomer to understand the invisible parts of a culture and misunderstandings around these aspects can be more confusing and uncomfortable in the moment.

Have you ever reflected on the invisible aspects of your culture?

The cultural tool kit

The cultural tool kit

Sociologist Ann Swidler proposed the concept of culture as a tool kit in 1986. In this metaphor, we use our cultural equipment or “tools” to inform our behavior and decision-making. Each person’s tool kit will be different based on their nature, context, and experiences. For example, your native language is one tool in your kit, along with any additional languages you may have learned. The tool kit metaphor helps us see how our personal cultures can shift and evolve when we enter a new cultural context. Tools that used to be very useful may be less so in the new context, and exposure to a different culture can be an opportunity to add new tools to our kit.

How has the make-up or use of your cultural tool kit changed since coming to the U.S.?

Tips for navigating a new culture

Dr. Darla K. Deardorff proposes a model for intercultural competence development that focuses on an individual’s cultural knowledge, skills, and overall attitude. While the pursuit of intercultural competence is a life-long journey, applying yourself in the following areas may lead to more successful and enjoyable intercultural interactions.

Knowledge

- Cultural self-awareness

- Culture-specific knowledge

- Sociolinguistic awareness

What can you learn about your host culture? Have you reflected on your own cultural background? Do you need to learn a target language, or perhaps develop knowledge of how the language is used where you will be staying?

Skills

- Observation

- Listening

- Evaluation

- Analyzing

What can you learn by closely observing your surroundings and listening carefully to what members from another cultural group have to say? Can you make connections from this information to the cultural knowledge and self-awareness you have developed?

Attitude

- Respect

- Openness

- Curiosity

- Discovery

Are you open to new experiences and respectful when you encounter difference? Do moments of misunderstanding or frustration spark a curiosity to dig deeper and discover more?

Culture shock & homesickness

Culture shock is defined as the set of emotions and physiological responses that result from having the familiar structures of one’s own culture taken away. For many people, culture shock is a normal and natural step toward cultural adjustment. Knowing what it might feel like to experience culture shock can help make the experience less isolating and more tolerable. Also, knowing when and how to seek support for yourself or a friend is key.

The experience of culture shock

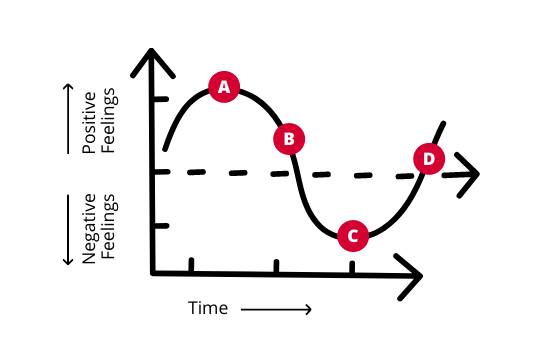

Culture shock graph

- Honeymoon Stage – “I love everything about the U.S.!”

- Disillusionment Stage – “Wow. The U.S. is really different from home.”

- Rock Bottom – “I don’t like the U.S. or the people here. I want to go home!”

- Realistic Contentment – “The U.S. is different, but I enjoy aspects of living here.”

Adapted from Brislin, R, & Yoshida, T. (1994) Intercultural Communication Training: An Introduction. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Symptoms & coping techniques

Culture shock symptoms & coping techniques

Feelings of homesickness generally fade as you move through the stages of cultural adaptation and realistic expectations for life and the host culture are established. While homesickness can return on occasion, time and self-care are usually all that is needed to cope.

That said, if you feel like your homesickness impacting your ability to engage with daily life, it might be time to seek out more help. The Counseling Center offers individual and group therapy along with other valuable mental health resources.

Lastly, you can always reach out to OIS. Many of our staff have lived or studied abroad and can empathize with your experiences with homesickness. Connect with an OIS advisor.

Common symptoms

- Sadness, loneliness, and melancholy

- Insomnia or sleeping a lot

- Depression, feeling powerless

- Anger, irritability, resentment

- Unwillingness to interact

- Feeling overwhelmed

- Loss of identity

- Inability to solve simple problems

- Lack of confidence, feeling inadequate

Ways to cope

- Stay connected with family and friends – Prioritize rich conversations by phone or video chat over messaging or social media. Schedule regular check-ins or a special Zoom date to have something to look forward to.

- Be mindful when using social media – We all know that social media can distort our perceptions of reality, especially when we are in a vulnerable time of life, like moving to a new country. Remember that the fun pictures of your friends back home or at another U.S. school likely represent a highlight reel of only the good moments. If your time on social media is making you feel worse, consider taking a break and replacing that time with in-person interactions.

- Keep your body moving – Go for a walk or exercise each day. Prioritize physical activity and notice how your body and mind feel when you are done.

- Evaluate your nutrition and sleep – Moving across the globe and into a new culture can significantly disrupt your eating and sleeping habits. You may find that behaviors you adopted in the short-term, such as fast food or jet lag-fueled late nights, have turned into your new normal and are now affecting your wellbeing. Focus on getting good nutrition and plenty of sleep to see if that helps your mood.

- Get involved on-campus – Attend a campus event, talk, or organization. Just being around others can help.

- Explore your new surroundings – Get to know your new home! Take a tour of campus or visit a new neighborhood, restaurant, or museum.

- Help others – Reach out to another international student or scholar to see how they are doing or if they need support. Use your experience to help others experiencing culture shock, both now and in the future.

- Avoid negative coping mechanisms – If you find yourself self-medicating with alcohol or other substances, cutting it out could improve your mood. If you find that you cannot stop, it could be an indication that you need additional support.